On a mild, late November morning, almost completely hidden behind the 5-foot-high walls of a sprawling, yellow-gray mud-brick city rising from the ground, a dozen members of an archaeological team survey and brush away soil.

In a nearby tent, carefully holding jagged pottery shards in one gloved hand under a lens, Asmaa Ebrahim painstakingly scribbles down notes on the 3,000th piece of pottery.

Traditionally, in this valley, rich with ancient Egyptian history and iconic archaeological sites, the role of ceramicist was filled by a foreign archaeologist with credentials from Cambridge or Princeton, not an Assiut University graduate from upper Egypt.

For decades here, Egyptians were the laborers, never the discoverers. But not on this dig.

“For once, Egyptians are the leading Egyptologists,” Ms. Ebrahim says, smiling.

As workers brush away dust and sand outside, a leather sandal pokes out from the ground, strap facing up, slightly sun-dried but looking as if it had fallen off the foot of its careless owner days – rather than 3,400 years – ago.

Today, in Aten, the recently discovered city at the foot of the Valley of the Kings, Ms. Ebrahim and a new generation of Egyptian archaeologists and specialists are uncovering fresh details of daily life in ancient Egypt and with them, newfound feelings of professional pride and overdue respect.

The discoveries are thanks to a new generation of Egyptian archaeologists trained and encouraged by Zahi Hawass, who is leading the dig at Aten. The colorful and bombastic former director of Egypt’s department of antiquities used his public persona as “godfather” of Egyptian antiquities to bring along 500 young specialists to staff all-Egyptian excavation teams.

Ms. Ebrahim is one of dozens who studied archaeology and Egyptology in Egypt and then, at Dr. Hawass’ urging, went abroad in the 2010s to work and train to gain technical expertise that Egypt lacked – in restoration, conservation, pottery analysis, carbon dating, and surveying.

Now they are back leading digs like this at Aten, grabbing headlines and changing the way the world looks at ancient Egypt.

On Jan. 26, Dr. Hawass’ Saqqara team announced the oldest-discovered mummy covered in gold, a nonroyal named Hekashepes buried 4,300 years ago.

“Our role as Egyptians cannot only be serving foreigners and bringing them coffee and tea while they write books and make films and we do nothing,” Dr. Hawass says as he walks along Aten’s serpentine wall. “We needed to gain the technical expertise that we relied on foreigners for.”

Inside the tent, Ms. Ebrahim’s eyes are fixed as if in a peaceful trance, fitting the iron caliper jaws on either end of the potsherd with a maestro’s precision.

Although humble, the 33-year-old admits she is an outlier: an Egyptian pottery specialist.

Despite their homeland’s wealth of historic sites that have captivated the world’s imagination for generations, archaeology is not a career of first choice for most Egyptians. Of the few that pick up a trowel, even fewer specialize.

The obstacles are many: There is little funding, and access to texts, journal articles, tools, and even software is difficult. Credit has long gone to foreign experts.

“It is not a job, it is a passion,” she says. “You have to be inspired to pursue it.”

It was a chance trip to the Cairo Museum with her family as an 8-year-old that sparked the Assiut native’s fascination with ancient Egypt, particularly the golden sarcophagi and ceramic vessels that had seemingly outlived the sands of time.

“When I saw these artifacts, I knew I wanted to study archaeology and help make rare finds, to hold the history in my hands,” Ms. Ebrahim says.

Now she holds up a blue painted vase with intricately carved gazelle heads poking out from either side – her favorite artifact from Aten.

Her Assiut university didn’t offer any pottery courses, so Ms. Ebrahim learned by volunteering with French and German excavations in Dahshour and Assiut. Those experiences taught her the importance of pottery analysis in excavating, interpreting, and dating sites and artifacts.

Inspired, she spent a decade relying on self-study, volunteer work, and foreign research institutes to develop an expertise in Middle and Early Kingdom pottery. Today, she is one of a handful of Egyptian ceramicists and the only onepiecing together the largest town ever unearthed from ancient Egypt.

“Pottery gives us a lot of information – it tells us the story, how old something is. When you piece together pottery, you piece together a people,” she says.

“Now we Egyptians can put the story of ancient Egyptians together ourselves.”

The story of daily life in ancient Egypt is coming together in Aten, the so-called Golden City.

Aten was the residential, administrative, and industrial center of ancient Thebes, dating back to the 18th dynasty and the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III – the golden age of ancient Egypt.

Discovered by chance while this rare all-Egyptian team was searching near Madīnat Habu for the mortuary temple of the “Boy King” Tutankhamen in 2021, it is now providing an ever-widening window into the daily life of ancient Egyptians.

Aten was abruptly abandoned by Amenhotep III’s son Akhenaten, when he transformed ancient Egypt’s religion and moved the capital 240 miles north of Thebes. That means much of the city was left intact as if life was suddenly frozen three millennia ago – Egypt’s own Pompeii.

Bread remains in clay ovens, precious stones are scattered in the jewelry workshop, and sun-dried bricks are neatly stacked in a tiny pyramid waiting to be carted off to build a temple or a palace.

A serpentine wall that experts believe was designed to limit Nile floodwaters cuts through the north of the city.

“We have bread in an oven; we have preserved meat, a sandal workshop. A complete residential life is depicted here in Aten,” Ms. Ebrahim gushes with enthusiasm, as she holds up a rare four-handled jug, “and it is not so different from our daily life today.”

Already the team has uncovered seven districts containing homes, a bakery, kitchens, a tailor’s shop, a weaver’s loom, a tannery, a metalsmith’s workspace, a sandal cobblery, and a butchery complete with dried meats in jars inscribed with the butcher’s name, Luwy.

The team is also uncovering technical clues about how ancient Egyptians built and furnished some of the wonders of the ancient world.

Its discoveries have included preserved amulet molds; a jewelry workshop; a brick factory; and granite, basalt, and pottery workshops. All of these, the team believes, were used to build and decorate Luxor’s lavish temples and palaces – and craft the ornate treasures buried in King Tut’s tomb.

New generationLowering the brim of his trademark olive-green fedora to shield his eyes from the rising Luxor sun, dig leader Dr. Hawass oversees the late morning progress in Aten – the discovery that is becoming a career-defining achievement.

With his outsize enthusiasm, bombastic personality, and flair for promotion – he sells replicas of his fedora for charity – Dr. Hawass has become synonymous with Egyptian archaeology over a four-decade career that has included stops as director of the pyramids at Giza, head of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, and minister of antiquities.

His career discoveries include two tombs in the Valley of the Kings and a workers’ necropolis at Giza, proving once and for all that Egyptians did build the pyramids.

But it is here, among bakeries and lost sandals, where the 75-year-old godfather of Egyptian archaeology is steering Egyptology into new horizons, bringing a generation of young Egyptian archaeologists and specialists along with him.

Although recent years have seen more joint international-Egyptian teams, his excavation is one where every role – from extracting and sorting soil to analysis to conservation – is done by Egyptians.

“As a young man entering a bookstore, I never found a single book on Egyptology written by an Egyptian. All our work depended on foreigners, and they took all the credit,” Dr. Hawass says. “But now we are a complete scientific team.”

After a Fulbright scholarship allowed him to complete his Ph.D. in Egyptology at the University of Pennsylvania – and see the vast libraries and resources Western scholars have access to – he returned to Egypt determined to develop archaeology back home.

The needs, to this day, are many: ceramicists, bioarchaeologists, archaeobotanists, surveyors. But Dr. Hawass’ long-range plan is slowly filling in the gaps.

In the early 2000s, he began a field work school to teach the basics of excavation techniques. His Fulbright experience inspired him to urge hundreds of Egyptian archaeologists and students to study, research, and volunteer abroad to gain the technical skills the country lacked.

Ms. Ebrahim was one such student, traveling to Germany and Poland through a scholarship from the Goethe Institute, where she learned digital database systems for recording artifacts, which she now uses to catalog finds from Aten and those at The Egyptian Museum.

“I always know they will come back. Who can resist this history in our homeland?” Dr. Hawass says as he stretches out his arms, Aten to his right, the Valley of the Kings to his left. “We have so much left to discover!”

Another core team member recruited by Dr. Hawass is Siham el-Bershawy, a Luxor native who grew up a few miles away from the Valley of the Kings and now preserves and restores everything from papyrus to mummies at Aten.

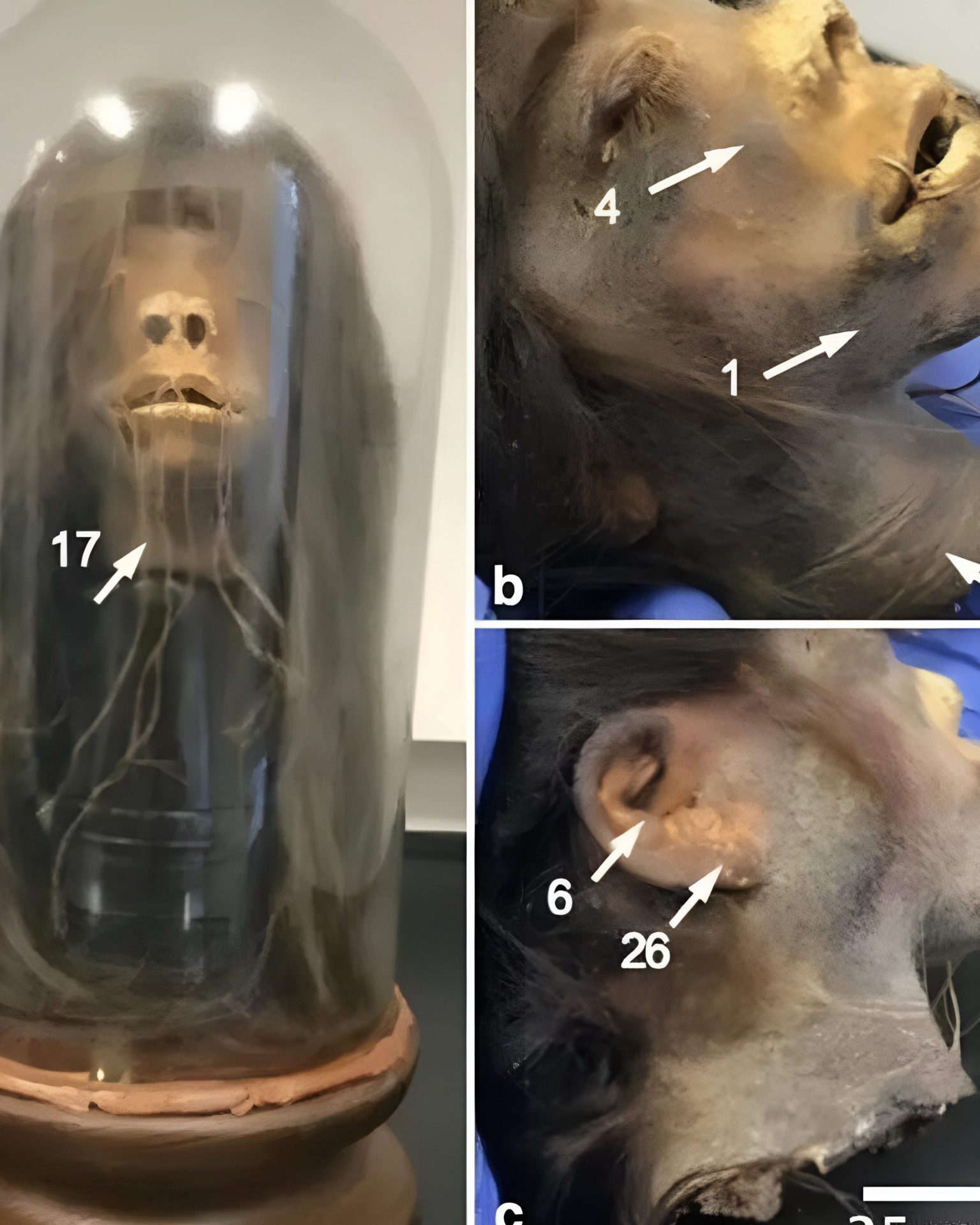

“That feeling when you take items out from the ground in your own site, in your own country, in your own community with your own two hands – you feel a sense of pride as an Egyptian,” Ms. Bershawy says as she adjusts the humidifier on a child mummy encased in glass in a tomb-turned-storeroom.

“It is your ability and skill that unearthed this item, and now you are the responsible one to protect it for future generations,” she says. “It is an awesome feeling.”

Earned RespectIt is also a recognition for Egyptian archaeologists that has been decades overdue.

Here in the Valley of the Kings, the names of foreign archaeologists still echo from history, such as Howard Carter, the Briton who excavated the tomb of Tutankhamen in 1922 and whose residence in Luxor is a top tourist destination.

In Aten, 2 miles west of the Carter House, this all-Egyptian team is expanding a discovery that many say rivals King Tut’s tomb, one that is earning accolades from academics and is listed as one of the top 10 discoveries of 2021 by Archaeology magazine.

With his all-Egyptian teams in place, Dr. Hawass is now accelerating excavations and discoveries at warp speed.

“The real mark we made in this city is to show for the first time the role of the young Egyptians who are leading in archaeology and Egyptology,” says Dr. Hawass.

Dr. Hawass’ second team, working in Saqqara, south of Cairo, last November discovered the funerary temple of Queen Nearit and 50 ornate wooden sarcophagi dating back 3,000 years to the New Kingdom – the earliest tombs discovered in that region.

“Two decades ago, we couldn’t compete with international teams. But now foreigners look to us with respect. For the first time we are seen on the same level as Western archaeologists,” Dr. Hawass says.

Other Egyptian Egyptologists making their mark include Monica Hanna, a leading heritage advocate pushing for the return of Egyptian artifacts such as the Rosetta stone, and Nora Shawki, a pioneer in settlement archaeology in the Nile Delta.

“I believe now we have more Egyptians who are interested in the history their country has and who are better trained to apply critical thought and professionalism to their excavations and the interpretations of their finds,” says Salima Ikram, professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo.

While Egyptian archaeologists may finally be having their day in the sun, there are still hundreds of key contributors who continue to labor in anonymity: the local laborers.

In Aten, just as in the time of Napoleon, they physically remove earth, carrying away quffa baskets full of topsoil. Egyptology rests on their shoulders too. Along with the new generation of archaeologists, workers deserve to be “celebrated,” says Professor Ikram.

Among the team’s most recent discoveries are five undisturbed tombs and five 4-foot-tall sealed jars at the edge of their excavations.

Dr. Hawass is planning to open one of the Aten tombs soon and is continuing fundraising to extend excavations west of the city.

Search for a queenAmong the details of ancient Egyptians’ daily lives in Aten, Dr. Hawass’ team has uncovered a royal clue, a name he believes may lead them to the lost tomb of Queen Nefertiti.

“Smenkhkare,” the name of a mysterious pharaoh who ruled briefly between Akhenaten and King Tut, was found on multiple inscriptions.

Egyptologists are divided on the figure. Some believe Smenkhkare may have been a brother to Tutankhamen or a hitherto unknown co-regent with Akhenaten.

Dr. Hawass is among those who believe Smenkhkare was a name assumed by Nefertiti after her husband Akhenaten’s death, when she ruled for three years as pharaoh.

While a separate British-Egyptian team is guiding a search for the lost queen’s tomb farther west in the Valley of the Kings, Dr. Hawass’ team believes that by following this clue, they may find it one day near Aten.

To Dr. Hawass, it would be a crowning achievement for Egyptian archaeologists, permanently etching their names in the pantheon of famous Egyptologists.

Already though, Aten has made a major contribution to Egyptology – and to Egyptian archaeologists being seen as peers.